Introduction to Neural Nets

Now that I got into this AI thing, many friends are asking me what artificial intelligence or neural nets are.

It is hard to give a concise answer to such a question while having a beer with a friend. But as I keep trying I have come to a version that is as short and as I think possible. It is maybe not the typical way neural nets are explained. Most books and tutorials on the web start describing mathematically the perceptron, it’s analogy with a neuron, and build up from here to a comprehensive view of neural nets. If you have the interest and the time you could check the introductions below:

- Neural networks on 3Blue1Brown YouTube channel

- Neural Networks and Deep Learning

- CS132n Lecture Videos

But that is too long to explain in five minutes in a pub, and I needed something shorter. Trying to condense these ideas has also made me understand better the fundamental concepts on neural networks too.

Pub explanation

Imagine you want a computer to perform a task, say recognize a cat from a penguin in a picture, or play chess. One way to do this is think how would you go about doing that, and try to describe it with code. The computer will then follow your mental processes. It is easy to see that while it sounds simple, it can turn to hell pretty quickly. Just as describing to a small child how to do something, you realize that some steps were trivial to you but the child doesn’t get it unless you go a level down in detail. And a computer doesn’t know anything, so you have to go down the most trivial thing. If you tell the computer it can recognize a cat by its fur, ears, or tail, you have to code what fur, ears, or tails are. And if fur is a cover of hair on the skin, you have to go and do the same with hair and skin. And when you finish with the cat you can reuse very little of your code for the penguin. You are basically on square zero if you now want your computer to recognize cars or sneakers.

Same with the rules of chess. However, while there can be unlimited cases of cat pictures, chess is a more delimited problem. After you describe the pieces and sit will chess experts to describe the best chess tactics, you more or less have it. So, it makes sense that programs could beat Kasparov in 1997, and fifteen years later they still could not distinguish an object in an image as well as any child can do.

Of course there are a lot of programmers and they have been busy coding and coming up with clever algorithms. So more and more tasks have been automatized and you would think eventually there will be a code for every single task, at what point computers will finally be our overlords and enslave or kill us all. But the hype explosion we hear in the media about AI now is not because of this linear progression. It is because of new much powerful general purpose algorithms, and these are the neural nets.

Now, what I find fascinating about neural nets is that the math they are based on is not that difficult to understand. Meanwhile I could not describe above in any detail the algorithms that IBM used to beat Kasparov at chess, because they are so complex and I don’t really know them. To me, there are four pieces to understand:

- The basic piece of a neural net is a collection of millions of numbers. Nothing special about those numbers yet. Just reserve a space, a box, on computer memory to store millions of numbers, and fill it randomly. There will actually be some boxes, but conceptually you can simply think of it as a big collection of numbers.

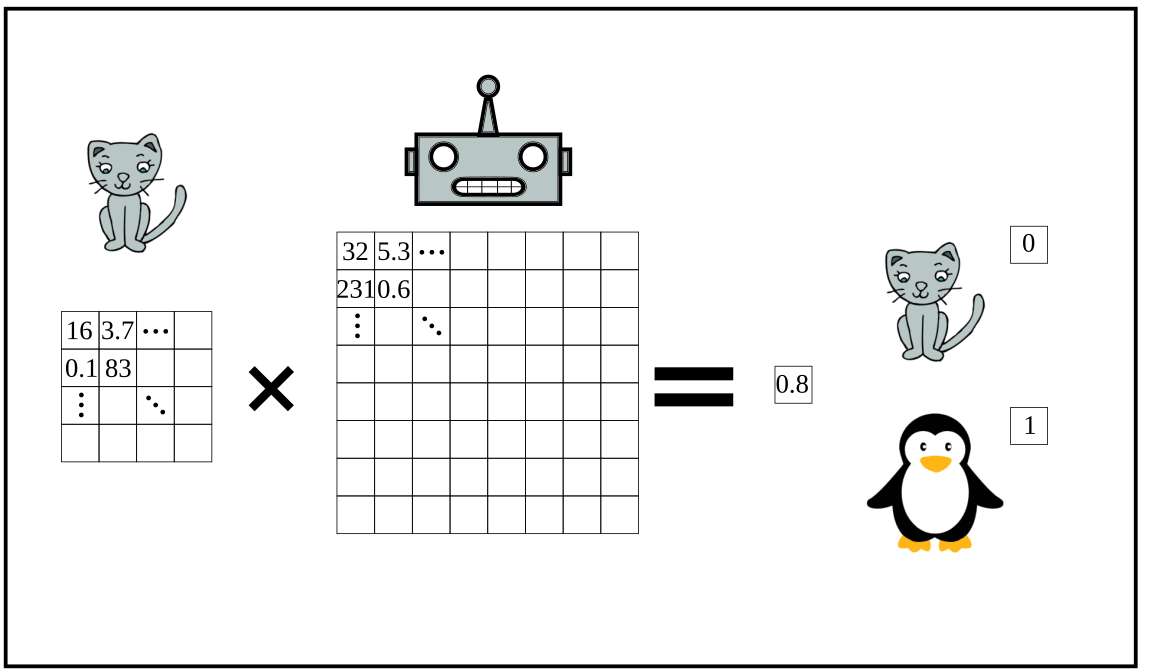

Now let’s focus on the image recognition example (cat or penguin). The images are going to be your input. You see images, but these are actually represented as numbers in the computer’s memory. So, you can do some mathematical operations, mainly multiplication, between the numbers of your input image and the millions of numbers in your boxes. You dispose these operations in a way that at the end of your operations you get just one number, say between zero and one, as a result.

So now that you have one number you say (quite randomly) that if you get one that means your computer has recognized your image as a penguin, and if it’s zero it would be a cat. And all values in between are the probability of cat or penguin. 0.8 means close to penguin, so 80% penguin 20% cat. As you can guess, it’s a matter of chance whether the computer is right or wrong. But at least we haven’t put a lot of effort programming this thing…

- Now, the second piece you need is a measure of how wrong the prediction is. As the probability the neural net gave to penguin is 80%, if it is actually a penguin you were only 20% wrong, and is it is a cat you were 80% wrong. The way you got to these values (the operations the net did) is just a function. This is a relatively easy function (called the loss function), because those millions of numbers are to a computer like a short equation to you.

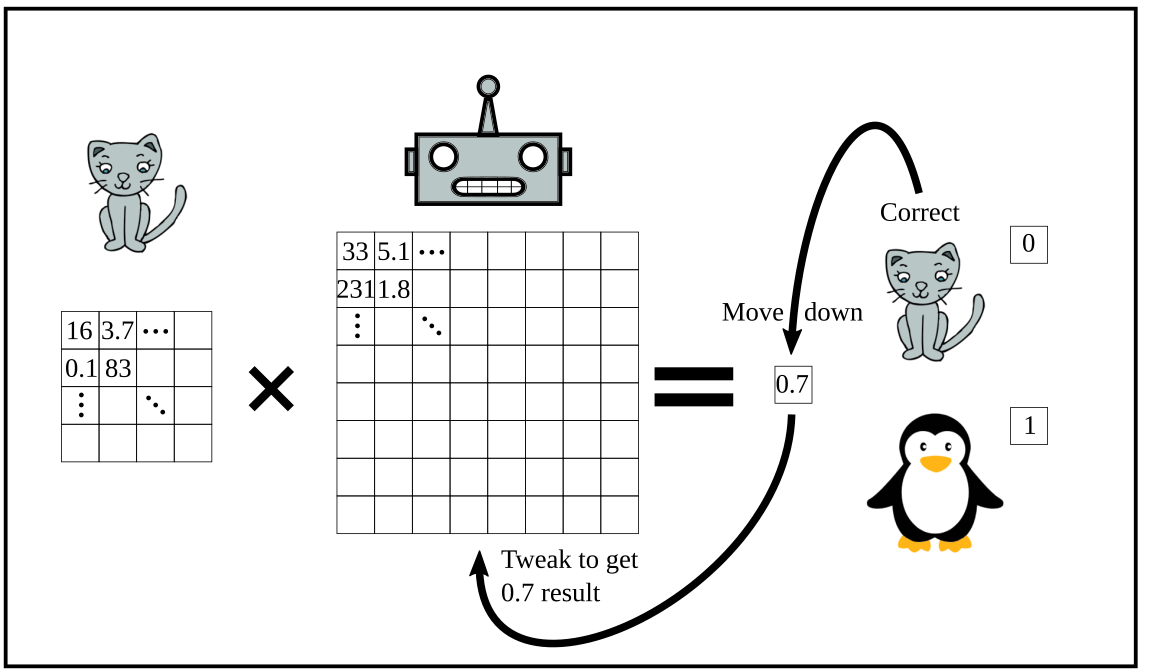

- The third part of the algorithm is to find a way to change a little those millions of numbers, so that you would have been a little less wrong.

As an example of what I mean, if the number in your box was 13, and you multiply it by the number of your image, which was 5, the result is 65. Now, if you want to actually obtain a result of 50 out of that your loss is 15. To reduce your loss, you have to change your number down in the direction to 10. Let’s say you change your number from 13 to 12.8 and you would be a little less wrong.

Here is the same, but with an operation that has some more steps (not that many actually), and millions of numbers. The difficulty is in those millions of numbers, but again, you have a computer, so let it just work and it will get the result in not so much time.

As you see, after this little change the network will still wrongly predict a penguin, but a little less wrong. That’s fine. We just want the network to learn something out of this image.

- Finally the fourth piece. You repeat this with lots of images. Not millions maybe, but tens of thousands would be good. Let the computer go through all the images, make it’s prediction, see what’s right, and change a little its numbers accordingly once and again, thousand of times.

And surprise, surprise! After some time the predictions get really good. You can show the algorithm an image it hasn’t seen on the training process and it will work. That’s it. That is the basic algorithm that is shaking the world right now and promising to give us self driving cars, exponential advances in medicine, and make computers our overlords that finally enslave and kill us all.

Why are they called neural nets?

There is an analogy to be done between this algorithm and the way the brain works. Usually all tutorials begin by explaining this analogy, as it sounds quite cool, and you can go deeper into the mathematics from the beginning. However the analogy is not perfect and I feel that giving it in a five minutes overview is misleading. It leaves the impression that neural nets are so complex as the human brain is, the layperson can never grasp it, and that’s why they are so powerful. But it is, as I say above, just a huge collections of numbers that gets adjusted by training automatically until they perform very well. And they perform amazingly well because we are talking of millions of numbers.

If it is so easy, why it didn’t happen long ago?

It happened long ago, actually. The first models based on the neuron analogy go back to the 40’s. On 1975 that third piece I talked about going back along yours operations to know how much to change your numbers (it’s called Backpropagation) was fully formalized. And in the 90’s Yann LeCun used this algorithm to develop a system to recognize handwritten numbers that was widely used to process bank checks.

However, for most applications, this algorithms where kind of a disappointment in you don’t use really a lot of numbers to adjust. So, computing power was an important bottleneck that got researchers quite unmotivated for many years (these periods are even officially named AI winters.

A second bottleneck was data. Maybe you don’t need millions, but it’s not so easy to have thousand of cat and penguin images (and dog, horses, faces, and what not), that are correctly labeled, so that our algorithm can learn from them. People had to do it the labeling manually first. You can hire some students for labeling the numbers for the LeCun system, and other images. Datasets were slowly growing that way, but then Internet came to help. At some point you had billions of people tagging their friends of their Facebook post and uploading the picture of the Linguine they had for dinner, for example, and basically doing the work for you.

And of course merit has to go to the researchers that stand through and survived the AI winters. They were ready to rekindle the fire when the conditions were good. Particularly, several of them found refuge in the University of Toronto. Here is a very interesting documentary about that.

Get into the details

What are those operations we apply?

I said before that we take the number of our images (inputs) and multiply by the numbers in our boxes… and some other operations. It’s not much complicated than that. Many of these other operations are improvements that researchers add to the basic algorithm to try to improve or adapt it to certain tasks. There is however one operation that belongs to the basic idea of a neural net: a filter or non-linearity operation.

This filter will get the result of the multiplication and turn to zero those numbers that are below a threshold level. Is is a nonlinearity because it treats the numbers in a non linear way. If the threshold is for instance 5, for a 12 the operation result is 12. For the half of it, 6, the result goes down linearly to 6. But for the half again, 3 below our threshold, the result goes suddenly to zero. So, that was non-linear.

This is the operation that brings to light the neuron analogy. The neurons get their inputs from the dendrites, that connect it to other neurons, and gives its output via its only axon. These are signals are electrical currents. Normally the neuron will be at rest, and only when the inputs from the dendrites sums up over a certain threshold, it will fire up and send a signal through its axon.

How many boxes do we really use?

This is the other detail I was not very exact in the pub introduction. You can have one box of number and get actually nice predictions. But it is not that good with only one box and is not actually a neural network. Or rather, it would be a network with only one component, which is quite a disappointment for a network. Take two boxes and you have a basic network formed by: Input –> Box 1 multiplication –> Filter –> Box 2 multiplication –> Filter –> Prediction

This second caveat completes the neuron analogy, because neurons are organized in layers. A neuron gets its inputs from other neurons through its dendrites, and send its output to other neuron through its axon.

Now that you have the basic components you can let your imagination run wild, specially if you are a researcher, and put more boxes in your network and apply different filters and operations to them. If you go deep and have more than 10 or 20 boxes, you will have a deep neural network, And you will be happy to see that, up to a certain depth, your predictions get really very good. The different ways you dispose your boxes, or matrices, of numbers will give you different network architectures. And some architectures will work better for some tasks than others. Here is a list of some important neural network architectures:

- Convolutional neural networks

- Recurrent neural networks

- Generative adversarial networks (GANs)

- Reinforcement learning

I have the personal program to make a project myself on each of these architectures to understand them from the bottom up. As I finish each of them I’ll try to share it and post an explanation of what is special about it. Wish me luck!